december 2014

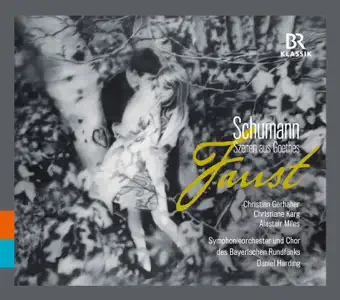

Robert Schumann: Szenen aus Goethes Faust, WoO 3

Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks o.l.v. Daniel Harding

Daniel Harding dirigeert met een geweldig gevoel voor tempo, gewicht en kleur en ondersteunt zijn eveneens goede zangers perfect in een werkelijk indrukwekkende live-opname.

Sinds Benjamin Britten er in 1973 een lans voor brak, heeft Scènes uit Goethes Faust niet geleden onder de stugheid van de koorvereniging die de vele charmes van Das Paradies und die Peri, Schumanns andere avondlange koorwerk, tenietdeed. Daniel Harding deed eerst Peri en dirigeerde vervolgens Faust met ‘zijn’ Zweedse radio-orkest in 2010.

Deze ervaring wijst allemaal op het goede. Afgezien van de blokkerige formaliteiten van de Ouverture (als laatste gecomponeerd, in 1853), is het snel duidelijk hoe tekstgedreven en lieddoordrenkt deze geweldige live-opname is. Toen mensen kritiek hadden op Schumanns orkestmuziek, bekritiseerden ze hem omdat hij niet Beethoven of Brahms was. Of het Beierse radio-orkest nu op volle sterkte is of niet – en de kathedraalscène van het eerste deel mist niets aan impact, geleid door Alastair Miles op zijn meest stentoriaanse als de Boze Geest – ze spelen met de gemakkelijke mobiliteit van een kamerorkest, gereduceerd maar niet minimaal vibrato en de dynamische terughoudendheid die nodig is om Schumanns specifieke orkestrale tinta te registreren met zijn nadruk op hout- en koperblazers aan de uiteinden van hun registers: de hoge piccolo's en lage trombones worden niet gebruikt om oppervlakkige hemel/hel-polariteiten weer te geven, maar als een schilderachtige achtergrond (naar het voorbeeld van Mendelssohn in De Hebriden, en in dit opzicht Gurrelieder vooruitlopend), waardoor Faust, de bariton in het midden van de foto, perspectief krijgt. De Duitse oratoriumtraditie lijkt minder relevant voor zowel het stuk als de opname dan de late doeken van Turner, zoals The Great Western Railway, waarin de mens op de rand van abstractie staat, alsof hij Goethes woorden voor Fausts dood zet. In Hardings koraalachtige akkoordplaatsing van de sublieme orkestrale epiloog van Deel 2, kunnen we zowel de Bach horen die door Schumann wordt opgeroepen als hij Goethes ‘Es ist vorbei’ vervangt voor de bijbelse echo’s van ‘Es ist vollbracht’, en, in zijn pijnlijke opschortingen, Mahler de liedjesschrijver. Gerhaher beweert dat deze vervanging laat zien hoe Faust door Schumann is gecanoniseerd, en roept kruismotieven in het Chorus Mysticus op als ondersteunend bewijs, maar ik hoor meer muzikale dan religieuze motivatie in het opus summum van een componist wiens geloof allesbehalve standvastig of conventioneel was.

Als Faust is Christian Gerhaher intiemer met ons en met Goethe dan op Harnoncourts opname, en zelfs (dit kan ketterij zijn voor sommigen) overtreft hij zijn leraar Fischer-Dieskau, die zoveel gevoel voor en ervaring met deze rol had. Naast de filosoof-koning kant van het personage, waarmee Gerhaher zich intellectueel thuis toont in een fascinerend interview dat is herdrukt in het boekje, heeft hij de charme van de plagende minnaar tot zijn beschikking terwijl hij in de tuin grapjes maakt met Christiane Kargs Gretchen. Zijn ‘Lebt wohl’ aan het einde van deze scène is een klein meesterwerk van spijt, hartstocht, bravoure en hoop, net zo rijk aan nuances als een mooi Marschallins ‘Ja ja’. Ondersteund door een aantal puntige dirigenten en prachtig in elkaar grijpende uitvoeringen van Gretchens standaard bekentenisscène, brengt Karg er een zachter, meer meegevend maar minder persoonlijk vocaal profiel in dan de doordringende trillerigheid van Elizabeth Harwood voor Britten.

Hardings trippende puls en teder getekende legato zijn ideaal voor het schemerige voorspel van Deel 2; en hoewel hij niet helemaal de Mendelssohniaanse magie van Abbado oproept, heeft hij Andrew Staples (de tenor voor zijn Peri-optredens), die als Ariel een verheven lijn en stemming beter vasthoudt dan de enigszins stijve benadering van Werner Güra voor Harnoncourt en de merkwaardig verkeerd gecaste Wagneriaanse tenor Endrik Wottrich voor Abbado. De kleinere rollen zijn allemaal goed ingenomen, maar in delen zoals het middernachtelijke scherzo is het het orkest dat nog meer zegt dan de zangers, met veel subtiele variaties van strijkersvibrato en blaaskleur. Centraal in Deel 2 staat Fausts verwonderde hymne aan de glorie van de natuur, en dit toont Gerhaher op zijn best, waarbij hij medeklinkers gebruikt om over zinnen heen te springen als stenen in een beek.

Gezien het feit dat de Scènes geen verhaallijn hebben om over te spreken, zou het zelfs nuttig kunnen zijn om ze te beluisteren zoals Schumann ze componeerde, achterstevoren, want het derde deel, begonnen in 1844, ademt een sfeer van aanhoudende inspiratie die nauwelijks minder ijl is dan het tweede deel van Peri van het jaar ervoor. De verhalende stroom die Harding (en Schumann) heeft meegegeven, is echter nog duidelijker en bewonderenswaardiger als het plechtige, Rijnlandse preludium van deel 3 wordt gehoord in het licht van het einde van deel 2. Hier breekt het koor los van vraag-en-antwoordconventies, krijgt gelukkig de juiste prominentie in de warme Herkulessaal-akoestiek en is goed in balans over de delen, zodat we kunnen genieten van Schumanns zwevende, zesde-getinte harmonieën. De jongens uit Augsburg zijn inderdaad zo 'gezegend' als Goethe gebiedt, helder, fragiel en perfect afgestemd.

Wanneer de Chorus Mysticus is bereikt, zorgt Schumanns apotheose – vloeiend en lichtgevuld gehouden door Harding – ervoor dat Mahlers setting in de Achtste net zo overdreven aanvoelt als zijn critici u willen doen geloven. Hier zijn geen ronddraaiende zonnen en planeten, maar een menselijke ziel die rust vindt. Over Schumann gesproken, Gerhaher merkt op dat ‘dit een versie van Faust is waar je je echt in kunt verliezen’. Over deze uitvoering kan ik alleen maar zijn gevoelens herhalen.

Since Benjamin Britten broke a lance for it in 1973, Scenes from Goethe’s Faust has not suffered from the choral-society stolidity that used to weigh down the many charms of The Paradise and the Peri, Schumann’s other evening-length choral work. Daniel Harding did Peri first, and then conducted Faust with ‘his’ Swedish radio orchestra in 2010.

This experience all tells to the good. Past the blocky formalities of the Overture (composed last, in 1853), it’s quickly apparent how text-driven and song-soaked is this marvellous live recording. When people criticised Schumann’s orchestral music, they were criticising him for not being Beethoven or Brahms. Whether or not the Bavarian radio orchestra is at full strength – and the cathedral scene of the first part lacks nothing in impact, led by Alastair Miles at his most stentorian as the Evil Spirit – they play with the easy mobility of a chamber group, reduced but not minimal vibrato and the dynamic restraint needed to register Schumann’s particular orchestral tinta with its emphasis on wind and brass at the extremes of their registers: the high piccolos and low trombones used not to represent superficial heaven/hell polarities but as a scenic backdrop (after Mendelssohn’s example in The Hebrides, and prefiguring Gurrelieder in this regard), lending perspective to Faust, the baritone in the centre of the picture. The German oratorio tradition seems less relevant to both piece and recording than the late canvases of Turner such as The Great Western Railway, in which man stands at the edge of abstraction, as if setting Goethe’s words for Faust’s death. In Harding’s chorale-like chord-placing of the sublime orchestral epilogue to Part 2, we may hear both the Bach evoked by Schumann as he substitutes Goethe’s ‘Es ist vorbei’ for the biblical echoes of ‘Es ist vollbracht’, and, in its aching suspensions, Mahler the songsmith. Gerhaher contends that this substitution shows how Faust has been canonised by Schumann, and calls up cross-motifs in the Chorus Mysticus as supporting evidence, but I hear more musical than religious motivation in the opus summum of a composer whose faith was anything but steadfast or conventional.

As Faust, Christian Gerhaher is more intimate with us and with Goethe than on Harnoncourt’s recording, even (this may be heresy for some) besting his teacher Fischer-Dieskau, who had such feeling for and experience of this role. Besides the philosopher-king side of the character, with which Gerhaher shows himself intellectually at home in a fascinating interview reprinted in the booklet, he has at his disposal the charm of the teasing lover as he banters in the garden with Christiane Karg’s Gretchen. His ‘Lebt wohl’ at the end of this scene is a small masterpiece of regret, ardour, bravado and hope, as rich in nuance as a fine Marschallin’s ‘Ja ja’. Backed by some pointful conducting and beautifully dovetailed playing of Gretchen’s stock confession scene, Karg brings to it a softer, more yielding but less personal vocal profile than the piercing tremulousness of Elizabeth Harwood for Britten.

Harding’s tripping pulse and tenderly drawn legato is ideal for the twilit prelude to Part 2; and while he doesn’t quite conjure the Mendelssohnian magic of Abbado, he has Andrew Staples (the tenor for his Peri performances), who as Ariel sustains an elevated line and mood better than the slightly stiff approach of Werner Güra for Harnoncourt and the curiously miscast Wagnerian tenor Endrik Wottrich for Abbado. The smaller roles are all well taken but in parts such as the midnight scherzo it is the orchestra who say even more than the singers, with many subtle variations of string vibrato and wind colour. At the centre of Part 2 is Faust’s wondering hymn to nature’s glories, and this finds Gerhaher at his finest, using consonants to spring across phrases like stones in a brook.

Considering the Scenes have no narrative thread to speak of, it might even be thought useful to listen to them as Schumann composed them, backwards, for the third part, begun in 1844, breathes an air of sustained inspiration scarcely less rarefied than the second part of Peri from the previous year. The narrative flow imparted by Harding (and Schumann) is even more evident and admirable, however, if the solemn, Rhenish prelude to Part 3 is heard in the light of the end of Part 2. Here the chorus breaks free from call-and-response conventions, happily given due prominence in the warm Herkulessaal acoustic and well balanced across the parts so we can relish Schumann’s hovering, sixth-tinted harmonies. The boys from Augsburg are, indeed, as ‘blessed’ as Goethe commands, bright, fragile and perfectly tuned.

When the Chorus Mysticus is reached, Schumann’s apotheosis – kept flowing and light-filled by Harding – does make Mahler’s setting in the Eighth feel as overblown as his detractors would have you believe. Here are no suns and planets revolving but a human soul finding rest. Talking of Schumann, Gerhaher remarks that ‘this is a version of Faust one can really indulge in’. Of this performance, I can only echo his sentiments.